I remember that the sand whispered and sound carried for miles. And dunes the colour of tanned skin – their perfect, female contours. I remember how the desert engulfed the town, dust blowing down narrow streets, gathering and drifting in doorways. There were blue men with pale eyes. They rode camels and carried swords and rifles. When they passed, they did not acknowledge us at all. There were tall palm trees, vegetables growing in beds surrounded by irrigation ditches. And in the ditches there were shoals of tiny, silver fish. I was following the 1947 journey of one of my heroes, Paul Bowles. I’ve always carried a book with me as a kind of totem. These days its Tranströmer’s Half-Finished Heaven, but back then it was Bowles’s Sheltering Sky. What drew me to it was the way the characters seemed to carry spaces inside them as vast as the landscape they were lost inside. It was how I felt about myself in my twenties. Bowles was a prolific letter writer. While holed up in a room during a 3 day sandstorm with only his parrot for company he wrote of the Sahara: “It is a great stretch of earth where climate reigns supreme and every gesture one makes is in conscious defence from, or propitiation to the climatic conditions . . . Man is hated in the Sahara. One feels it in the sky, in the stones, in the air.” I didn’t write any letters home and I took no photographs. All that remains of my Sahara journey is an old French Michelin map and a line, as thin as my footsteps, that I drew in biro, linking the names Taghit, Timimoun, Adrar, El Golea.

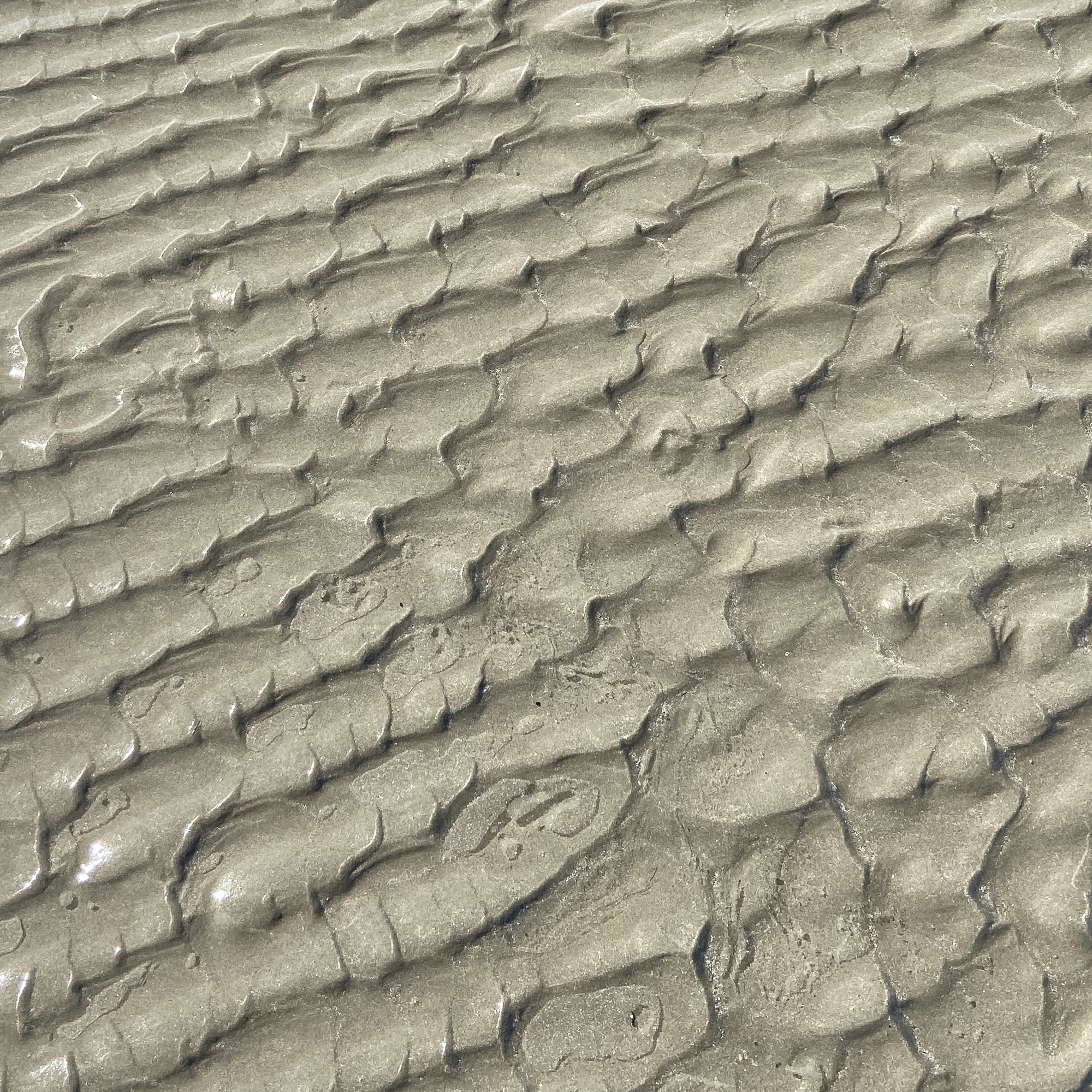

Another thing I remember, waking one morning to see a track crossing the sand in front of my tent, tiny indentations, footprints of some four, six or eight-legged thing which had skittered across the dunes in the night. As I traced the line up to the dune’s crest a breeze started up. Within seconds the footprints had disappeared. Is this a definition of how to live well on this earth, that it should be able to erase our tracks with one breath?

During R.S. Thomas’s long life he struggled with his relationship to God, enduring long, doubt-filled periods spiked with surges of belief. Passionate about non-human life, he reached the opinion that the evidence for the presence of God was to be found in the still-warm form of a hare, a hollow in the turf which still resonates with the creature’s presence after it has gone. I have never encountered one. I see hares regularly on the hill but they are always halfway to the vanishing point before I spot them. I can never work out where they sprang up from, perhaps a doorway out of another world. I appreciate Thomas’s elegant image. Since the enlightenment we’ve been peering ever closer at nature, revealing and decoding its secrets, harnessing its power to our own ends. Along the way we got to know the work of our gods too well and fell out of love. Reverence requires vast empty spaces.

A few years before my journey into the desert I was stranded on an island, that is what family holidays felt like to me. To survive I had brought an A2 pad of paper and some pencils. During the afternoon hours I walked to a shaded ravine where I sat and drew the strange, spiny plants that grew from the rocks. At first it was an effort to capture the complex interlacing shapes of leaves and seed heads, an exercise to learn the patience I’d never had. But I grew frustrated with the process quickly and started to draw thick dark lines roughly in the direction of the plant’s growth, only to then attack the marks with a rubber, almost, but never completely, erasing them. After an hour of this process the accidental result was something resembling a tree in fog, an apparition floating in white space. It’s the only drawing I’ve ever done that I’m proud of. Fujiko Nakaya makes sculpture with fog. The fog drifts, thickens and thins, people gain and lose their orientation, an intense experience which leaves some in tears, others shaking with fear. Nakaya believes that the fog makes things more visible: the environment, the cyclical processes of nature, life and death. To give depth to a thing, you sometimes have to erase it. Another artist Peter Von Tiessenhausen was asked to donate work to an exhibition at a gallery in Sarnia. He agreed to contribute a large cast iron bust as long as it was buried beneath the street in front of the gallery building. The bust still resides there, subterranean and invisible, filling the surrounding area with mystery. What could be more dreary than a bust pristinely displayed on a pedestal in a white room? And what could be more powerful for the imagination than the same bust entombed in the earth a metre below your feet?

My favourite time of year is in the late autumn when cloud descends low over the valley. You can climb a hill and walk above the mist, a river-sea of whiteness stretching between high ridges. These treeless hills are almost empty, almost all of the time, but the patchwork in the valley is a constant reference to their taming. When the mist is down the mystery is restored. Wales is a country over-populated with absences. In the uplands, miles of stripped heaths dominate, pocked with the remains of people who have gone before us. These lands sing of their longing through the voices of buzzards. But nobody’s listening. Down in the valley windows glow with flickering lights.

We live in the age of the microcosm. Having lost our sense of mystery we spend our days digging into ever smaller spaces. Our attention narrows as words start to fall from our language. Though we’re endlessly creative we’ve yet to harness that creativity to tame our destructive capacities. Therefore the lands around us desertify. The Sahara has spread by 1.5 million square miles in the past century and a further 650,000 square miles of productive land has been lost in Africa in the past 50 years. Soil depletion in places like Wales is accelerating. Some studies have estimated that we only have 60 harvests left. Emptiness is on the move. In these days of climate change and biodiversity loss it is moving faster. I don’t know what’s coming, but the stories of Paul Bowles are starting to look prophetic, with their lost, self-obsessed characters roaming landscapes where even the stones hate us.